“The international community perceives the Plurinational State of Bolivia as a country that is successfully mitigating the extractive boom while upholding the rights of Indigenous communities in the protected territories. This, however, is very far from the truth,” says Miguel Miranda, Advocacy Coordinator at the Bolivian Centre for Documentation and Information (CEDIB).

On a recent mission to verify illegal mining activities in one of the largest protected areas in the world, Senator Cecilia Requena and her associates were threatened with kidnapping and assaulted with stones, firecrackers and dynamite. The attack occurred in Madidi National Park when illegal miners targeted members of the Senate’s Land and Territory Committee and representatives from Amazonian Indigenous organisations. It is one of more than two hundred attacks against defenders documented in a new database.

“The violent aggression that occurred yesterday, in the middle of a trip to inspect illegal mining settlements, highlights the terrible normality of subjugation, illegality, abuse, impunity, ethnocide and ecocide in Bolivia.”

–Senator Cecilia Requena (via Twitter)

Mapping attacks against environmental defenders in Bolivia

CEDIB is closely monitoring the human rights and environmental situation and has found evidence of a large number of violence and attacks against those defending the rights and territories of communities and their protected areas. The threats and attacks are mostly against women, carried out with impunity and primarily within the context of extractive activities in the region.

HURIDOCS supported CEDIB and the National Coordination for the Defence of Indigenous Peasant Territories and Protected Areas (CONTIOCAP) with the development of a documentation system that maps the direct threats and violations against environmental defenders.

The system architecture consists of three synchronised Uwazi databases, each with a specific function: data collection, information organisation/analysis and communicating public information. “This approach makes it easier to compartmentalise and keep confidential data secure, while simultaneously allowing certain information to be shared and published publicly,” says Salva Lacruz, HURIDOCS’ Programme Manager in Latin America.

The public database was launched at an online event in April 2022. The Map of Attacks against Environmental Defenders exposes the details of more than 200 recent cases of threats and violence and is updated continuously. The cases are related to nearly 200 perpetrators who have threatened or attacked close to 50 victims. Each of the infractions is geolocated and categorised into eight broad incident types: denial of access to information, extortion and coercion, smear campaigns and defamation, restrictions on freedom of expression, harassment, denial of civil and political rights, denial of access to justice, and violence.

Investigating four micro-regions

To investigate the harmful effect of extractive and related activities on the protected territories, CEDIB has teamed up with CONTIOCAP to work in four large micro-regions: the Amazon, Chiquitanía, El Chaco and Tierras Altas/Altiplano. In each of these regions, teams on the ground are trained to collect, monitor and document information and testimonies that will be used for preparing statistics, presenting evidence and producing in-depth reports. This documentation process aims to be objective, truthful, and to show the real impact of the extractive industry on the human rights situation and the environment in Bolivia.

According to Miguel Miranda, the collection of primary information is a complex process and the affected areas are vast. The impact of the extractive activities on the different regions is not fully assessed — that is why a database mapping the violations in the different regions is crucial.

“The collaboration with CEDIB provided the HURIDOCS team a valuable learning experience about the context of work for the defence of territories and communities in Bolivia, both in its technical and political aspects. We applaud CEDIB and CONTIOCAP for their commitment to exposing the lack of justice and accountability for defenders and the environment in Bolivia, and for their efforts to raise awareness about the ongoing violations.”

–Salva Lacruz, Programme Manager for Latin America, HURIDOCS

Trampling of human rights and the environment

Many of the Indigenous territories and protected areas in Bolivia are rich in mineral resources. Research conducted by CEDIB indicates that the extractive activities are not properly regulated and cause irreparable harm to the communities whose lives and livelihoods depend on the land. Activities such as mining, agribusiness and hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation pose a danger to the future and sustainability of the communities and territories. There are numerous examples of extractive activities imposed on Indigenous communities and territories without due processes followed.

“According to the information recorded by our organisation, during this year the government has decided to irregularly and even illegally promote a large number of extractive activities, to the detriment of the environment and the rights of Indigenous peoples.”

—CEDIB Report on Human Rights in Bolivia, January to March 2022

CEDIB’s quarterly report on the human rights situation in Bolivia reveals that the problematic human rights climate is caused by a complex combination of issues: lack of justice and accountability, political persecution, a continuation of extractive activities, violence, corruption, polarisation, social conflict and human rights violations.

According to Miguel Miranda the information in the database details incidences of violence and attacks that occurred over the past six years. It relates to two broad categories: violations against human rights, environmental and territorial defenders, and actions to advance extractive projects that negatively impact the environment.

Violations against human rights, environmental and territorial defenders

Bolivia has a diverse and multi-ethnic population: almost half of the population belongs to the 36 recognised Indigenous groups. Indigenous communities are the custodians of the region’s biodiversity and the caretakers of its natural resources. They are also dependent on the environment for survival and the preservation of their culture.

Indigenous communities are the most affected by extractive activities and associated ills such as unrestricted illegal mining, extractive exploitation, an increase in violence by irregular armed groups linked to illegal mining, and drug trafficking. In their attempts to counter these activities, the defenders, their organisations, Indigenous leaders, community members and journalists are subjected to aggression, intimidation, harassment, coercion, blackmail, defamation, attacks on physical and psychological integrity, arbitrary arrests, and denial of justice.

CEDIB is deeply concerned about the situation and reported previously that “most of these attacks go unpunished and have a devastating effect on those doing important work to defend human rights and the environment”.

Strong laws, weak implementation

Bolivia’s legal framework dealing with Indigenous peoples’ rights is hailed as both revolutionary and exemplary. Bolivia is a signatory to the ILO Convention 169, an international legal instrument dealing specifically with the rights of Indigenous and tribal peoples. In 2007, Bolivia became the first country in the world to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) into domestic law. The 2009 Bolivian Constitution, considered one of the most forward-thinking constitutions in Latin America, mirrors many key areas and provisions of UNDRIP.

The principle of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) is enshrined in the ILO Convention and the UN Declaration and is referred to as free, prior and informed consultation in the Bolivian Constitution. FPIC is not only a right but also a good practice to ensure that Indigenous communities’ rights are respected in the planning and implementation of projects affecting the use of their land and resources.

The standard of FPIC, as well as Indigenous peoples’ rights to lands, territories and natural resources, are embedded within the universal right to self-determination. It affords Indigenous peoples the right to say no. They can accept, reject, partially accept, or choose not to give an opinion on a proposal. They can also request as much time as they need to decide what is best for them and their territories, and they can withdraw consent at any stage.

In the Bolivian context, there are many indications that FPIC is merely an administrative check-box. In an interview with CIVICUS, CONTIOCAP’s Ruth Alipaz Cuqui explains that the Convention, Declaration and Constitution represent progress on paper only. She maintains that FPIC is manipulated and turned into a simple administrative process without proper consultation with those who are affected by the activities. “It consists of drawing up minutes and signing forms and allows the participation of groups close to the government, which the government identifies as valid interlocutors even though they are not the real people affected by the projects in question,” she says.

Notably, Bolivia passed Law 071 of 2010, better known as the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth. This was followed by the more extensive Framework Law 300 of 2012 of Mother Earth and Integral Development for Living Well. These attempts to recognise the rights of Mother Nature (Pachamama) as a living entity demonstrate that, at least in principle, Bolivia is dedicated to the cause of protecting the natural environment. But these laws have been heavily criticised for not being implemented or enforced, and are generally seen as being a ‘toothless’ novel legal construct.

Eleven years since Chaparina

This year marks the eleventh anniversary of the violent attacks at Chaparina when national police openly assaulted Indigenous protesters who were against the construction of a government-proposed highway through the TIPNIS Indigenous Territory and National Park. More than a decade later the government continues to intervene in judicial processes while persecuting political opponents, silencing critical voices, inhibiting human rights defenders and restricting journalists.

(Photo by AFP. Source: paginasiete.bo)

The Indigenous communities and territories of Bolivia are doubly violated: on the one hand the protected areas are being destroyed, pillaged and polluted, while on the other hand those who are trying to stop these activities are silenced, threatened, abused and attacked. It is becoming increasingly difficult for activists, defenders and journalists to express dissent and seek justice for the Indigenous communities, territories and the environment.

Extractive projects that negatively impact the environment

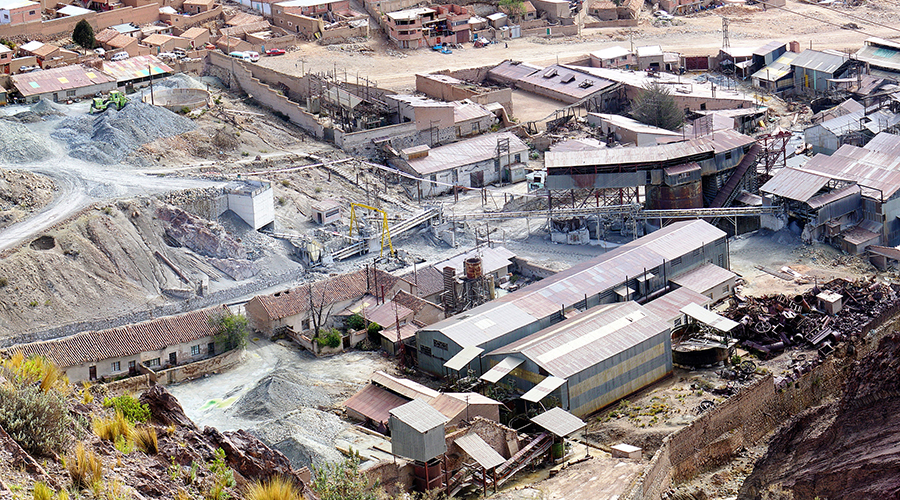

Mining is one of Bolivia’s most significant economic activities and the country relies heavily on its hydrocarbons sector, where natural gas is drilled for export and domestic use. Economic growth slowed down in 2014 because of a decline in the international prices for the country’s export commodities. To try and ignite the economy, the Bolivian government turned to hydroelectric power generation and increased its extractive activities.

There are many reports that the government is partial to the extractive industry, and stifles dissent by individuals and organisations that protect and defend the rights of the people and the environment. Operators in the mining sector are known to be aligned with government officials and wield economic and political power, act with impunity and carry out extractive activities without due process.

The impact of the explorative and exploitative seismic activities is far-reaching and poses a serious threat to biodiversity and conservation. Bolivia’s topography, climate and social vulnerabilities make it even more susceptible to the negative effects of climate change.

Social conflict amidst promises of wealth

Community members are often divided when it comes to reconciling conservation with development. Bribery, blackmail, coercion and the promise of development coupled with financial gain sow division among the Indigenous communities and are a primary cause for social conflict. Ruth Alipaz Cuqui says that the Indigenous peoples have been mentally colonised and the promise of great wealth never materialises.

“We must understand that the wealth that is generated in our territories is taken by outsiders and their corrupt environments. Behind the facade of interculturalism, the government divides us to discipline us and put us at the service of its political interests.”

–Ruth Alipaz Cuqui, CONTIOCAP

Water scarcity and contamination as a result of mining

Community members in Tariquía Flora and Fauna National Reserve have reported incidents of victimisation, hostilities, interference, threats and harassment. Testimonies indicate that public officials disguise themselves as protesters in an attempt to intimidate those advocating for environmental justice and the right to a clean environment.

Tariquía provides water to the southern parts of Bolivia and a community of more than 3,000 depend on its natural resources for survival. Despite being an important source of water the state-owned Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales Bolivianos (YPFB) is seeking to revive its exploration activities in the reserve.

In Roboré, located in the Chiquitanía region, the negative impact of extractive activities on the environment is evident. Rampant fires, wood trafficking, deforestation and settlements have significantly reduced the availability and quality of water in the area. The residents of the Roboré Municipality are now forced to search for groundwater sources to supplement the dwindling supply of uncontaminated water.

Reconciling conservation with development

On 28 July 2022, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a historic resolution declaring that access to a clean and healthy environment is a universal human right. The resolution comes at a time when economic and environmental interests are increasingly at loggerheads.

“The resolution forms part of the collective fight against the triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution. The resolution will help reduce environmental injustices, close protection gaps and empower people, especially those that are in vulnerable situations, including environmental human rights defenders, children, youth, women and Indigenous peoples.”

–UN Secretary-General António Guterres

Mandating full human rights impact assessments

In a 2020 country report, the United Nations Independent Expert Juan Pablo Bohoslavsky notes that there is a clear need for comprehensive and robust legislation on human rights impact assessments for infrastructure projects in Bolivia. He concludes that the current FPIC processes fall short of international human rights standards and may have a significant impact on the human rights of affected communities, particularly the human rights of Indigenous peoples.

He further recommends that the government of Bolivia should establish comprehensive and robust legislation that mandates a full human rights impact assessment for any infrastructure project and meaningful consultations with potential or actual affected communities. This should be done in line with international human rights law and standards.

Read the shadow report by more than 50 civil society organisations prepared for the Third Cycle of the Universal Periodic Review of Bolivia (2019) before the United Nations Human Rights Council.

Living in harmony with nature

How do we ensure a sustainable future where communities can thrive whilst maintaining a healthy natural environment? Can we successfully balance the interests of nature conservation and economic progress? Are conservation and development mutually exclusive? How do we achieve the goals of sustainable development where access to justice and accountability is elusive?

“The environment and the economy are really both two sides of the same coin. If we cannot sustain the environment, we cannot sustain ourselves.”

–Wangari Maathai, Kenyan environmentalist and Nobel Peace Laureate

There is more and more pressure on governments to make sure that there are collective efforts in place to promote and ensure climate justice. States are required to monitor, enforce and implement environmental laws, while individuals and communities should respect, claim and defend their environmental rights. Achieving a sustainable future and a healthy environment depends on appropriate legal frameworks, the just regulation of development activities, as well as meaningful and regulated consultation processes.

The right to a clean and healthy environment is everyone’s responsibility but duty bearers should ensure that this right is realised for all current and future generations.